Aaron Willard dish dial tall case clock. Boston. ZZ-41.

Aaron Willard made this very colorful cross-banded mahogany tall case clock in Boston, Massachusetts. This is a historically significant example. It retains the casemaker's stamp, printed onto the backboard inside the case. It can be viewed through the waist door opening. This stamp belongs to Henry Willard, Aaron's son. Henry is thought to have made numerous cases in the Massachusetts clockmaking community. There are six examples of this unusual and distinctive case form currently known. This very late form represents some of the last tall cases produced in Boston. Many of the design elements exhibited in this design are closely related to the Massachusetts dish dial shelf clock form that Aaron Willard made and sold so well.

This high-style example features mahogany construction. The mahogany veneers are positioned so that the excellent grain patterns accentuate the case form. The appropriate shellac-based finish has been restored and is transparent. The result is that the fancy grain patterns of the wood selected are on full display. This case stands on four flared French feet. They retain their original height and elevate the case off the floor three inches to the bottom center of the drop apron. A thinly applied molding visually separates the feet from the base. The mahogany veneer selected for the base panel is positioned vertically. This figured panel radiates with long sweeping grain lines. The central panel is framed with a cross-banded border along its perimeter. This design element is repeated in the construction of the rectangularly shaped waist door. This door is also trimmed with a simple applied molding. The door opens to access the interior of the case. Here, one will have the necessary access to regulate the clock for time. The adjustment is performed by turning the knurled nut at the bottom of the brass-faced pendulum bob, "Lower is Slower."

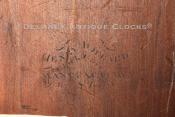

Henry's cabinetmaker's stamp is also found inside the case. Henry Willard used this stamp occasionally. It reads. "Henry Willard / Clock Case / MANUFACTURER / 843 / Washington ST. / Boston." This stamp appears to have been done with a transfer of ink. A tiny percentage of the Willard clocks with this stamp survive today. This stamp positively identifies the cabinetmaker and is a seldom-seen addition to the history of the clock. How many items do you know of that are made by father and son?

Fully turned smooth quarter columns flank the sides of this case and are fitted above veneered blocks. These terminate in brass quarter capitals. The flat-top bonnet features a very fancy and lacy open fretwork design. Three reeded plinths support this. Each plinth is capped at the top and fitted with a brass finial. Fully turned bonnet columns visually support the upper bonnet molding. These are mounted in brass capitals. A large diamond pattern of drilled holes is located on the side panels. Red silk covers the back of the holes inside of the case. The purpose of this hole pattern is to allow the hour-strike sound to escape the case's interior. This decorative and helpful detail is often associated with Henry Willard's cabinet shop. The bonnet door is veneered with figured mahogany. This door is fitted with glass. The glass is painted and decorated from the back. This pattern is a recurring theme on other Willard clocks. Most commonly, it is found on dish-dial shelf clocks made by numerous clockmakers of the period. Musical harps are centered in the corners or spandrel areas. Gilt leaves are also included in the design. All of the details are backed in red paint. The frame is painted black, and gilt borders define the detailed areas. This hood door opens to access the dial.

This iron dial is a concave form and measures 12 inches in diameter. This indented dial format became the standard in the construction of shelf clocks during this period. Arabic numerals mark the quarter hours and are positioned outside the closed minute ring. Inside the circle, large Roman-style numerals are used to mark the hours. A subsidiary seconds dial is located in the traditional location. Please note the wonderfully shaped steel hands that indicate the time. This clock does not have a calendar feature. The Maker's signature can be found in this location. The signature reads, "Aaron Willard / BOSTON."

The movement is constructed in brass and is of good quality. Four turned pillars support the two large brass plates. The hardened steel shafts support the polished steel pinions, recoil escapement, and brass gearing. The winding drums are grooved, and the weight cord is tracked in an orderly fashion. The movement is weight-driven and designed to run for eight days fully wound. This clock retains its original red-painted tin can weights. The movement is a two-train or a time-and-strike design with a rack and snail striking system. As a result, it will strike each hour on the hour. This is done on a cast iron bell mounted above the movement. It is interesting to note that the hammer is returned to the ready position via a coil spring. The coil spring return is an American feature. This clock also retains its original wooden rod pendulum and brass bob.

This fine example is nicely proportioned and stands approximately 7 feet 11.5 inches or 95.5 inches tall to the top of the center finial. This clock is 19.5 inches wide and 10 inches deep when measured at the feet.

This clock was made circa 1815.

Inventory number ZZ-41.

Aaron Willard was born in Grafton, Massachusetts, on October 13, 1757. Little is currently known of Aaron's early life in Grafton. His parents, Benjamin Willard (1716-1775) and Sarah (Brooks) Willard (1717-1775) of Grafton had eleven children. Aaron was one of four brothers that trained as a clockmaker. In Grafton, he first learned the skills of clock-making from his older brothers Benjamin and Simon. It is recorded that Aaron marched with them in response to the Lexington Alarm on April 19, 1775, as a private under Captain Aaron Kimball's Company of Colonel Artemus Ward's Regiment. Aaron re-enlisted on April 26 and was soon sent by General George Washington as a spy to Nova Scotia in November. By this time, he had reached the grade of Captain. He soon returned to Grafton to train as a clockmaker. In 1780, Aaron moved from Grafton to Washington Street in Roxbury along with his brother Simon. Here the two Willards establish a reputation for themselves as fine clock manufacturers. They were both responsible for training a large number of apprentices. Many of these became famous clockmakers in their own right. The Willards dominated the clock-making industry in the Boston area during the first half of the nineteenth century. Aaron worked in a separate location in Roxbury from his brother and, in 1792, relocated about a quarter-mile away from Simon's shop across the Boston line. Aaron is listed in the 1798 Boston directory as a clockmaker "on the Neck," His large shop employed up to 30 people, while 21 other clockmakers, cabinetmakers, dial and ornamental painters, and gilders worked within a quarter-mile radius by 1807.

Some important dates for Aaron Willard include...

1783, Aaron married Catherine Gates. They have two children. The first is Aaron Willard Jr who becomes a very accomplished clockmaker. Catherine Gates dies in 1785.

1789, Aaron marries Polly Patridge. Polly has two sisters that also marry clockmakers Abel Hutchins and Elnathan Taber. Aaron and Polly have nine children. Two work-in-the-clock trades. George Willard 1817-1821 becomes a journeyman clockmaker. Henry Willard (1822-1887) trained as a cabinetmaker and made cases for the Willard operation when he came of age.

1792, Aaron builds a large home at 143 Washington Street in Boston. He lives in this house until he dies. This house is also the location of his workshop. A barn is converted into an area to finish wood. Other spaces in the carriage shop are rented to related artisans.

1802-1804, Aaron is in a business partnership with cabinetmaker James Blake as Willard & Blake. Aaron's position is financial.

1804, Aaron he transforms the carriage house and barn into a workshop space for artists, clockmakers, woodworkers, etc. It is now known as Willard's Compound.

1805-1806, Aaron is a financial backer in the partnership of Willard & Nolen. Spencer Nolen (1784-1849) is an ornamental artist who begins painting clock dials. In 1808, Spencer Nolen married Aaron Willard's daughter.

1823, Aaron Willard retires. He is 66 years old.

1844, Aaron died on May 20 and is buried in the Eustis Cemetery in Roxbury.

We have owned a large number of tall case clocks made by this important Maker. In addition, we have also owned a good number of wall timepieces, some in the form of banjo clocks, gallery clocks, as well as numerous Massachusetts shelf clock forms.