Jesse Emory of Weare, New Hampshire. A mechanic, farmer and an ingenious wooden geared clockmaker. The finest wooden geared Clockmaker in America. AAA-12.

Jesse Emory was born on July 17, 1759, in Weare, New Hampshire. He was the son of Caleb Emory of Amesbury and Susannah (Worthley). Jesse is reported to be the first male born in that town and one of the first New Hampshire-born Clockmakers. At the age of twenty, Jesse enlisted in Captain Lovejoy's company for the defense of Portsmouth. Jesse married twice. His first marriage was to Hannah Corliss in November of 1783. She bore him one daughter, Ruth. His second marriage was to Betsy Wyman of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, in February of 1786. Jesse purchased 27 acres of land from Jeremiah Corliss, his first father-in-law. This land and a single building were located on Mt. Dearborn Road in Weare near the Henniker town line. He operated a business here until 1806, when he moved to the neighboring town of Deering. He sold the land in Weare to his daughter. The Town Histories of Henniker and Weare and the deeds recorded for the land transactions made lists him as a mechanic, farmer, and yeoman. He is reported to have made spinning and flax wheels, measures, harnesses, and clocks. He was also a skilled cabinet and clockmaker, making the entire clockworks and cases out of locally grown wood. The vast majority of the clocks found are fitted with thirty-hour pull-up movements. (One eight-day key wind example has been identified.) The movements are constructed in maple. The dials are skillfully painted on maple and are signed "Jesse Emory / WEARE" or "Jesse Emory / of / WEARE." Both styles are known. The decoration and details on the dials are often incised to prevent paint bleeding. Emory also constructed his clock cases. These are typically made of birch or maple woods. A high percentage of these have been found that are decorated with grain-painted features. Several of his cases incorporate a unique door latch design. Very few clocks have been found by this ingenious Maker. Approximately 12 clocks are recorded. Jesse died on July 10, 1838. He was 79 years old.

Jesse Emory is best known for the high quality of the wooden geared movements he made. They are considered superb machines and continue to perform above most expectations. They are framed with two large, heavy plates. These are highly finished and are supported with five turned and shaped wooden posts. This framing is secured to the seat or saddle-board with a handmade wooden screw. This is oversized and threads through the seat-board into the center of the lower middle pillar or post that supports the movement. All of the gearing is considerably oversized as compared to other Makers of the day. The largest of the wheels, the two great wheels, are approximately an inch thick. The designs of these wheels also included three gravity clicks on each of the winding arbors rather than the typical spring click and or ratchet mechanism. The clicks are inset in the wheels and simply fall into place as designed as the arbor turns when wound. Each wheel in the gear train is finely finished. Many are designed with an undercut detail. The strike train features a count-wheel. This is positioned at the back of the movement. Like the vast majority of wooden geared clocks, this example is designed to run 30 hours on a full wind before running out. It will strike each hour on a cast iron bell mounted above the movement.

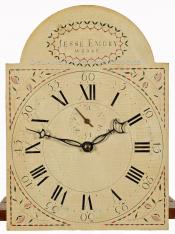

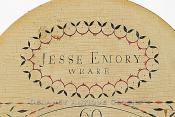

The dials of Emory clocks are handmade and skillfully painted on a maple blank. This dial is signed "Jesse Emory / WEARE" in the arch. The maple blank features two large battens that are attached to the back of the dial. These serve two purposes. The first is to prevent the dial from warping. The second purpose is to provide a convenient mounting point between the dial and the movement. The entire dial is treated with a red wash. The front or display area is painted white. The paint is heavy and is nicely finished. Many of the painted decorative details are laid into the dial. In other words, Emory took the time to lightly engrave much of the dial decoration before he applied the colors. The incising of the dial was probably done in order to prevent the bleeding of the paint. The four predominant colors used include black, red, pink, and blue/green. The time is displayed by two tulip-formed pewter hands. These have been painted black. The time track is formatted with Arabic five-minute markers along the outside edge. Dots are used to delineate the minutes. Large Roman-style numerals are used to mark the twelve-hour positions. Inside the time ring in the traditional location of the seconds registrar is a month calendar display. This is not an unusual detail for a wooden geared clock.

The case is formatted in the traditional woods and proportions that one would expect from the Concord, New Hampshire region circa 1790. This case is constructed in maple and retains much of its original red wash surface. The tones are excellent, and the surface presents a soft and warm feel. This case stands on applied bracket base molding that rests flat on the floor. The base section forms a box. The front edges are dovetailed together. The dovetail joints are displayed on both sides. This is a fantastic construction detail that is time-consuming to produce. The waist section is long and is fitted with a large tombstone-shaped waist door. Through this, one can gain access to the two soapstone drive weights and pendulum. The weights are eight-sided. One winds this clock by raising these daily by pulling down on the free string. The pendulum retains its original wooden rod and cast iron bob. The pendulum swings into and out of a pocket that is constructed inside the case. This is a very unusual detail. I am not sure what purpose it serves. If you buy this clock, you may be the only person who has a clock with this unusual design feature. The bonnet can be easily described as a swan's neck form. This example is better shaped than most. The moldings are heavily formed and terminated in carved rosettes. Three turned wooden ball, and spire finials are mounted on plinths at the top of the bonnet. The finials are fantastic and original to this clock. Tombstone-shaped side lights are positioned in the sides of the hood feature tombstone-shaped side lights. These are both fitted with glass. The dovetail case construction is also on display here on the sides of the case. The dovetails are large and very well made. The bonnet columns are turned smooth and subtly shaped. The bonnet door is an arched form and is fitted with glass.

This New Hampshire masterpiece stands approximately 7 feet 2 inches tall to the top of the center finial. The case is 22 inches wide and 11.5 inches deep, measured at the upper bonnet molding. This clock was made circa 1795. It is the Duesenberg of the American Wooden geared clock world.

Inventory number AAA-12.

Jesse Emory of Weare, New Hampshire. A mechanic, farmer, and an ingenious wooden geared clockmaker. He is renowned for creating some of the finest Wooden geared clocks in America, a significant achievement in a time when clockmaking was a highly respected craft.

Jesse Emory was born on July 17, 1759, on Craney Hill in Weare, New Hampshire. He was the son of Caleb Emory, originally from Amesbury and Haverhill, MA, and Susannah (Worthley (1740-1835)). His parents moved to Goffstown and then to Weare around 1758. Jesse is reported to be the first male born in the town and one of the first New Hampshire-born Clockmakers. At the age of twenty, on September 20, 1779, Jesse enlisted in Captain Lovejoy's Company for the defense of Portsmouth. He was discharged two months later. Jesse, a farmer and a mechanic, was living in the northwest corner of Henniker near Weare when he married Hannah Corliss on November 20, 1783. She bore him one daughter, Ruth. Hannah's brother was James Corliss, who owned a gristmill downstream and would become a competitor of Jesse's in the clock business. On February 18, 1794, Jesse purchased 27 acres of land and a building on Mt. Dearborn Road in Weare near the Henniker town line from his father-in-law, Jeremiah Corliss. He set up shop here in a business-friendly section called Meadowbrook. Jesse manufactured clocks from this location until early 1806. Emory was a complete clockmaker, producing his own movements, dials, and often cases. All of which were made to the

highest standards. Jesse stayed there until 1806, when he sold some land in Weare and moved to Deering, NH. The Town Histories of Henniker and Weare and the deeds recorded for this land transaction listed Emory as a mechanic, farmer, and yeoman. He is reported to have made spinning and flax wheels, measures, harnesses, and clocks. It is speculated that he moved because of the competition from James Corliss and Abner Jones, who were making clocks nearby. On July 19, 1806, Jesse bought approximately 50 acres in Deering from Jonathon French. Jesse's second marriage was to Betsy Wyman of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, in 1814. On October 3, 1826, Jesse purchased 34 acres of land in Henniker from Jonathan Green. This land became the Emory farm on Peasley Road. Jesse died on July 10, 1838, at the age of 79. His gravesite is not currently known.

Emory was a skilled cabinet and clockmaker. His design and execution are that of legend. He made the entire clockworks and cases for each out of wood. Eleven of the twelve clocks recorded are fitted with thirty-hour pull-up movements. (One eight-day key wind example has been identified.) The works are constructed entirely of maple. The large, heavy plates are highly finished and are supported with five turned and shaped posts. This framing is secured to the seat-board with a wooden screw that threads into the middle pillar or post of the movement. The robust gearing is oversized. The largest of the wheels, the great wheels, are approximately an inch thick. The wide wheels allowed for large teeth that increased the surface area for each tooth. This made them stronger and added to the longevity of the works. These wheels are undercut and incorporate three gravity clicks on each of the winding arbors rather than the typical spring, click, and ratchet mechanism. The clicks fall into place as designed. Each wheel in the gear train is finely finished. Many are designed with an undercut detail. The escapement is a recoil, a mechanism that controls the motion of the gear train. The hour hand and date hands are driven from the minute hand through gearing. The strike train features a count-wheel positioned at the back of the movement.

The dials of Emory clocks are handmade and skillfully painted on a maple blank. The dials are often signed "Jesse Emory / WEARE" in the arch. Other examples are signed "Jesse Emory / of / WEARE." The white background is polished and smooth. Many of the painted details are laid into the dial. In other words, Emory took the time to engrave the dials before he applied the colors. The incising of the dial was probably done to prevent paint bleeding. The four-color decoration includes black, red, pink, and blue/green. Emory also constructed his cases, which are typically made of birch or maple wood. A fair number of these retain their original grain-painted surfaces. A number of his cases incorporate a unique door latch. Very few clocks are known by this ingenious Maker. Approximately 12 clocks are recorded.