Joseph Ives of Brooklyn, New York. The Brooklyn Model shelf clock. SS-15.

The Brooklyn Model was made between the years 1825 and 1830. Joseph Ives had moved from Bristol, Connecticut, to Brooklyn sometime before 1825. This example is a fine representation of the types of clocks he was producing. They are not only interesting looking but incorporate several uncommon features in their movement design.

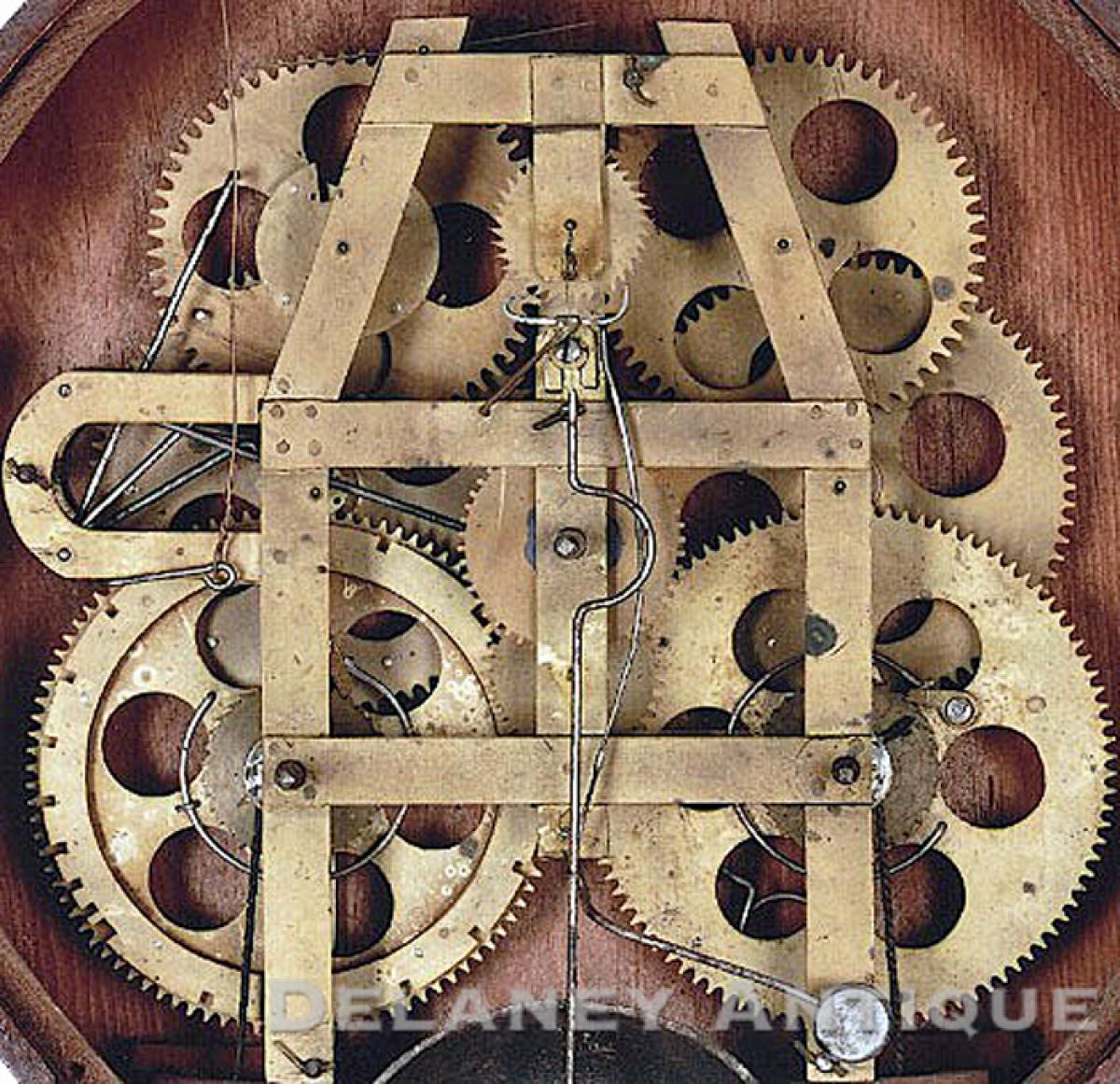

The movement is constructed with narrow straps of rolled brass that are riveted together. Brass was not readily available in large quantities, and this structure was economically feasible. Another attempt to conserve valuable brass material is the process of punching out circular holes in the gears plates instead of being left solid. The main wheels have five cutouts, each suggesting this movement may be a transitional example. The latter clock features only four holes in this location. The earliest Brooklyn models feature five holes but are framed differently. The strike side features a great wheel fitted with a 24-hour countwheel that is riveted in place. The pinion design features rollers. This movement is powered by a unique system of cantilever-actuated springs. These are leaf springs. They are fastened to the bottom board of the case with a bracket and bolt. When tensioned, the power from the leaves is transferred to the movement through a hoist and a lever. Enough energy is tensioned in the eight iron leaves to run this model for eight days. However, 30-hour examples of this leaf or wagon spring power source require as few as three leaves. This eight-day version also features a strike train that will strike each hour on a cast iron bell mounted inside the case.

The case is constructed of mahogany which is veneered over pine. The new tradition of the stylish and up-to-date Duncan Phyfe furniture produced in New York influences the form.

The case is elevated on four feet. The two at the back are turned into a cone design and dowelled into the bottom board. The front feet are carved in the form of animal paws. The hairy paws consist of four toes and are skillfully formed. The lower section, or the base, features a large door that provides access to the pendulum. One can also view the unusual power system. Pasted to the backboard is the Maker's label, which includes the setup instructions for this model. The lower door frames a wonderfully figured mahogany veneered panel. The middle section of this clock case is decorated with repousse brass floral-themed medallions. They are framed in circular wooden-turned moldings that are stained black. The dial is protected by a brass bezel that is fitted with glass. The bezel is hinged and opens to access the hands and the winding squares. The dial is paper and applied to a wooden blank. This paper dial is in excellent original condition and features the Maker's name and working location. The time ring measures 10 in diameter. It has two-minute rings that frame the Roman-style hour numerals.

This very interesting clock has the following dimensions. The case measures approximately 29 inches tall, 15 inches wide, and is under 4 inches deep. The dial measures approximately 10.5 inches in diameter.

Inventory number SS-15.

Joseph Ives was born on September 21, 1782. He was one of six children born to Amasa Ives, who married into the Roberts family of Bristol, Connecticut. Gideon Roberts is recorded as the first clockmaker to have worked in Bristol, and it is now thought that he trained his five sons in clockmaking and possibly trained Joseph and his brothers in the trade as well. They all would have been trained before Gideon died of typhoid fever in 1813.

Joseph Ives began making wooden geared clocks about 1811 in East Bristol. Shortly after that, he moved to Bristol and continued in the trade. The type of clocks being manufactured was called “wag-on-the-wall” or hang-ups.” Peddlers who could carry a small number of them on horseback sold these across the countryside. A hang-up consisted of a movement, dial, hands, weights, and pendulum. They were generally sold without cases because of the added cost and the difficulty in transportation. As a result, most cases were made locally. Ives clocks are distinctive in that they typically feature rolling lantern pinions instead of leaf pinions in their movement design. This was an Ives improvement that was patented.

By 1820, Eli Terry was enjoying great success in selling the 30-hour wooden geared shelf clocks of his design. Terry’s clocks were powered by weights, and Ives began to experiment with a spring-powered version having roller pinions attached to a wooden movement. Due to financial difficulties, Joseph moved to Brooklyn, New York about 1825 and worked on Poplar Street. Here he begins the production of a movement constructed with rolled brass strips which are then riveted together to form the movement frame. Roller pinions and the leaf spring power are also used. The case of these clocks has a Ducan Phyfe furniture influence.

In 1830, Ives creditors caught up with him again, and he was on the verge of being sent to debtors prison. John Birge hears of this and travels from Bristol to Brooklyn to settle his debts and to persuade Ives to return to Connecticut to make clocks, first with C. & L.C. Ives, who were using his strap frame design and then with John Birge under Birge & Fuller name. This company used the leaf or wagon spring power in many clocks. This design of power was also patented by Ives.

Joseph Ives sold the rights to his patents and continued to work in the clock fields under various firms. He was never financially successful but is credited as one of the most ingenious Connecticut horologists. Joseph died in 1862.

For a more complete description of Joseph Ives and his working career, please read, The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810-1862, written by Kenneth Roberts.