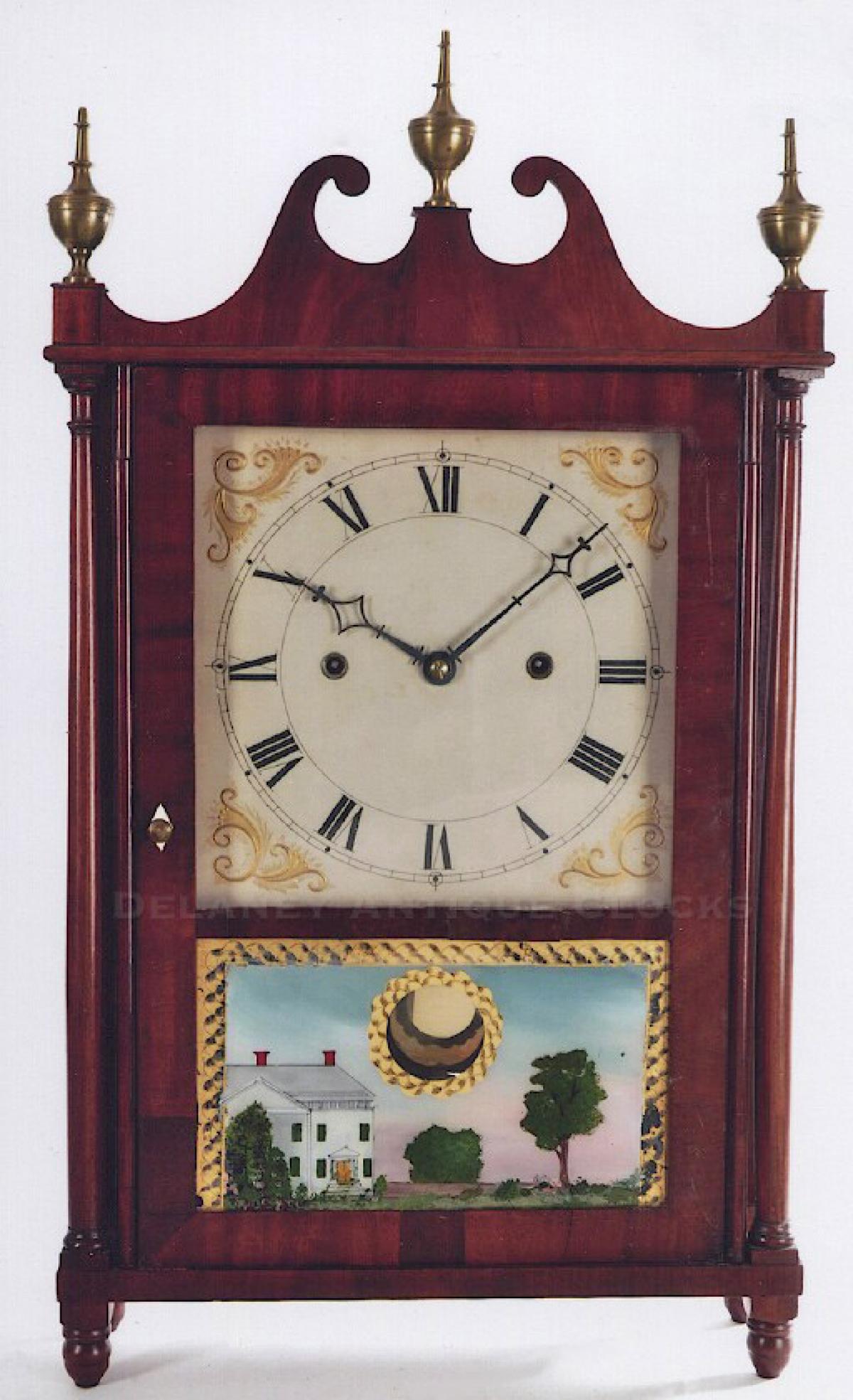

Joseph Ives pillar & Scroll. Rare. Lever or cantilever spring powered. TT-187.

Joseph Ives of Bristol, Connecticut, made this mahogany-cased Pillar & Scroll clock. It is very unusual in that it features experimental power. This example is powered by a cantilever spring of Ives design and is one of approximately six known. It was made circa 1818. According to Ken Roberts, "with the possible exception of a brass movement musical shelf clock reportedly made by Thomas Harland, this may be the earliest spring actuated clock made in Connecticut."

The case form is similar to Terry's design. The scroll top, brass urn finials, free-standing turned columns, Reverse painted lower door tablet, painted wooden dial, and wooden geared movement are all similar elements. This case stands up on turned feet. This clock is approximately 27.5 inches tall. This example is marked in ink "12" on the back of the dial and along the front edge of the seating board; the top edge of the door is marked in pencil "74".

The movement is wooden geared and designed to run for approximately 30 hours. It features roller pinions, an iron rod escape wheel, a pallet bridge, and a count-wheel strike. The cast iron bell is mounted at the top of the clock outside the case. In the lower section of the case is considered to be a prototype of Ives' cantilever spring. The cherry winding drums measure approximately 5.25 inches in diameter. The cord attaches to the movement barrel and the iron lever spring.

For additional literature regarding this clock and other Ives clocks, please see Kenneth D. Roberts, The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810-1862. It illustrates and discusses a related example on pages. 40, 43-44.

Provenance: Collection of Dick Babel, New Woodstock, New York. Exhibited at the American Clock and Watch Museum, Bristol, Connecticut.

Inventory number TT-187.

Joseph Ives was born on September 21, 1782. He was one of six children born to Amasa Ives, who married into the Roberts family of Bristol, Connecticut. Gideon Roberts is recorded as the first clockmaker to have worked in Bristol, and it is now thought that he trained his five sons in clockmaking and possibly trained Joseph and his brothers in the trade as well. They all would have been trained before Gideon died of typhoid fever in 1813.

Joseph Ives began making wooden geared clocks about 1811 in East Bristol. Shortly after that, he moved to Bristol and continued in the trade. The type of clocks being manufactured was called “wag-on-the-wall” or hang-ups.” Peddlers who could carry a small number of them on horseback sold these across the countryside. A hang-up consisted of a movement, dial, hands, weights, and pendulum. They were generally sold without cases because of the added cost and the difficulty in transportation. As a result, most cases were made locally. Ives clocks are distinctive in that they typically feature rolling lantern pinions instead of leaf pinions in their movement design. This was an Ives improvement that was patented.

By 1820, Eli Terry was enjoying great success in selling the 30-hour wooden geared shelf clocks of his design. Terry’s clocks were powered by weights, and Ives began to experiment with a spring-powered version having roller pinions attached to a wooden movement. Due to financial difficulties, Joseph moved to Brooklyn, New York about 1825 and worked on Poplar Street. Here he begins the production of a movement constructed with rolled brass strips which are then riveted together to form the movement frame. Roller pinions and the leaf spring power are also used. The case of these clocks has a Ducan Phyfe furniture influence.

In 1830, Ives creditors caught up with him again, and he was on the verge of being sent to debtors prison. John Birge hears of this and travels from Bristol to Brooklyn to settle his debts and to persuade Ives to return to Connecticut to make clocks, first with C. & L.C. Ives, who were using his strap frame design and then with John Birge under Birge & Fuller name. This company used the leaf or wagon spring power in many clocks. This design of power was also patented by Ives.

Joseph Ives sold the rights to his patents and continued to work in the clock fields under various firms. He was never financially successful but is credited as one of the most ingenious Connecticut horologists. Joseph died in 1862.

For a more complete description of Joseph Ives and his working career, please read, The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810-1862, written by Kenneth Roberts.