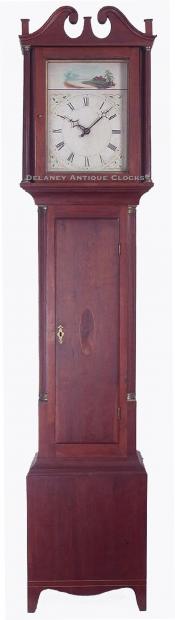

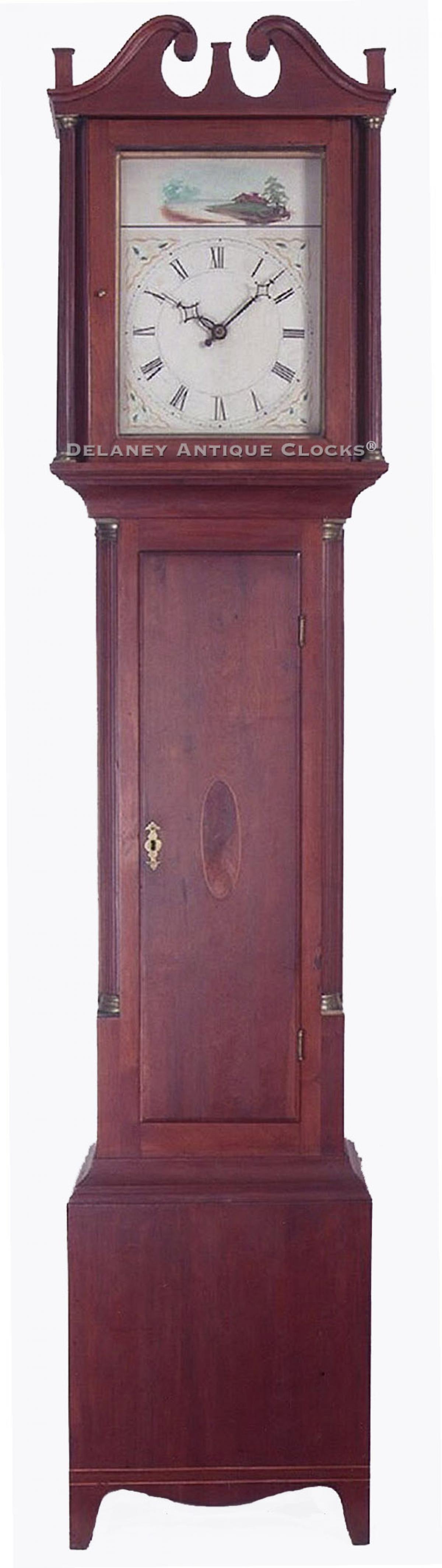

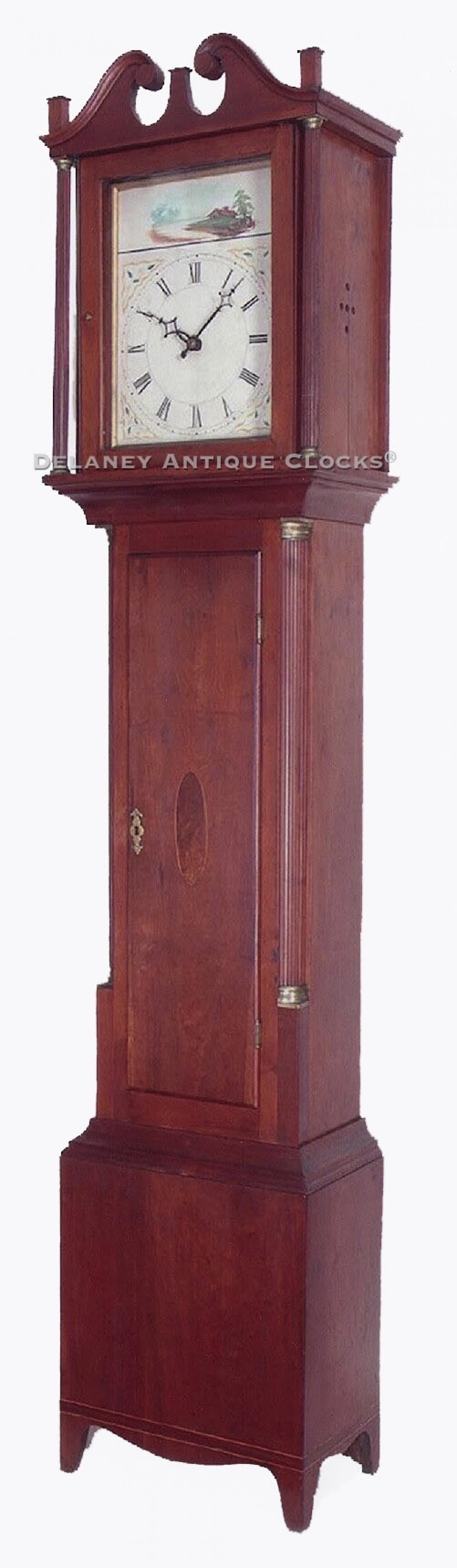

Joseph Ives tall case clock. 8-day wooden geared movement. Bristol, Connecticut tall clock. 23145.

This is an important tall case clock having a wooden geared movement made by Joseph Ives in Bristol, Connecticut. It is an outstanding example. Very few examples of Ives tall cases exist today. (Another example is exhibited at the American Clock & Watch Museum, which is located in Bristol, Connecticut.)

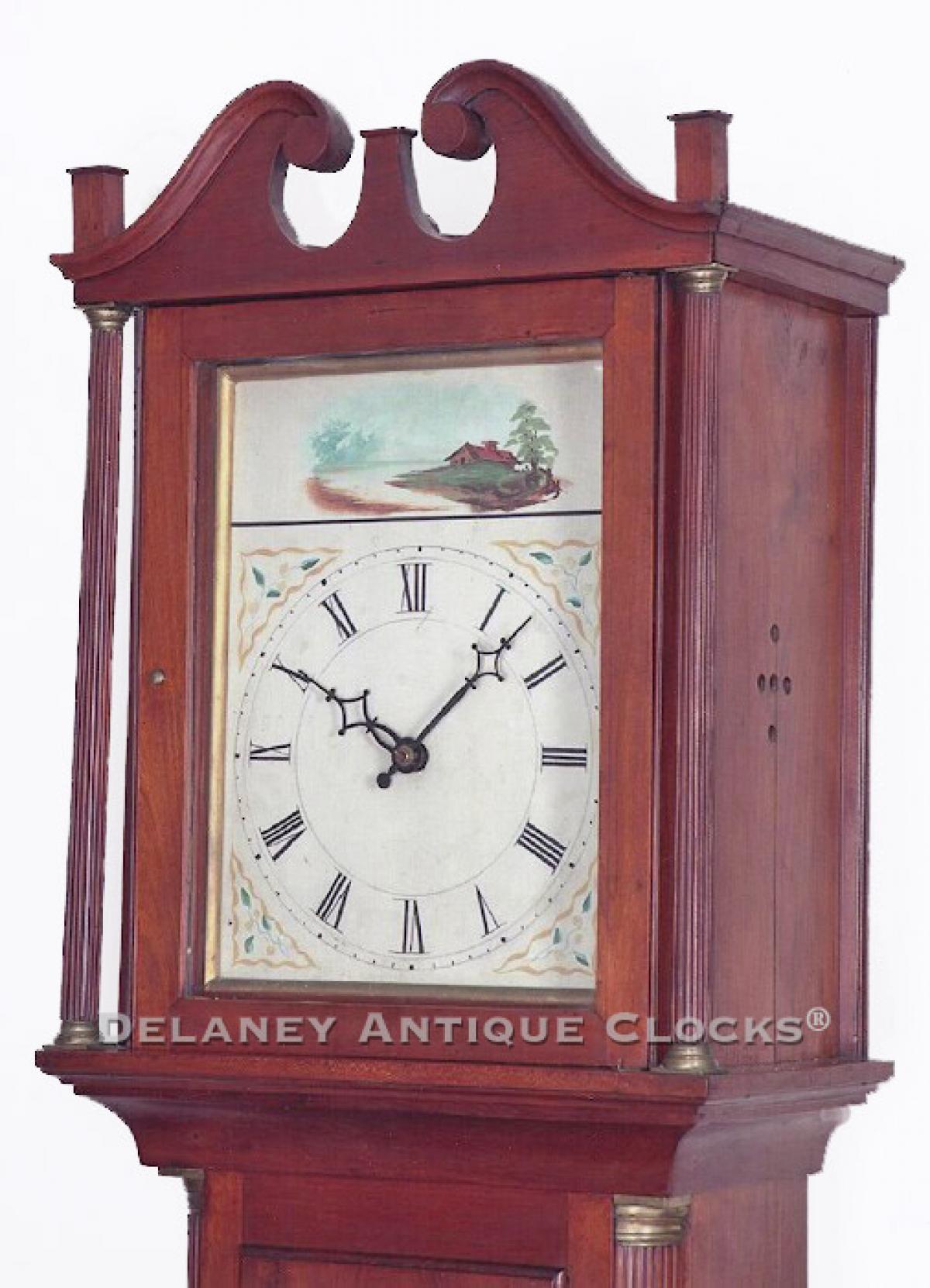

This case is constructed in woods that are indigenous to New England. The primary wood is cherry. It is inlaid with maple, and the secondary wood is white pine. The case retains an older finish which presents the case in a wonderful mellow tone. Four cutout bracket feet raise the case up off the floor. They are visually separated from the base by a horizontal line inlaid pattern. A drop apron hangs down from the center section of the base. The waist is long and features a rectangular door that is trimmed with a simple molded edge. The center is inlaid with an oval framed with a delicate line inlay of maple. The wood selected for the oval form is richly grained and shows well in this location. Open this waist door, which locks on the left, and one can access the two tin can weights and the pendulum. The sides of the waist are fitted with fluted quarter columns. These terminate in brass quarter capitals. The bonnet features a swan's neck pediment. The arches are nicely formed and decorated with a simple molding that ends in a plain rosette. Three capped plinths are located at the top of the bonnet. These were never fitted with finials. The bonnet columns are fully turned and fluted. These are mounted in brass capitals. They visually support the top of the bonnet. The bonnet door is rectangular and fitted with glass. The sides of the hood have been drilled in a simple diamond pattern. This is to allow the sound of the bell to escape the case.

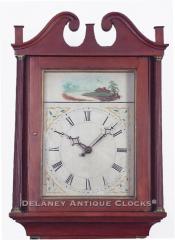

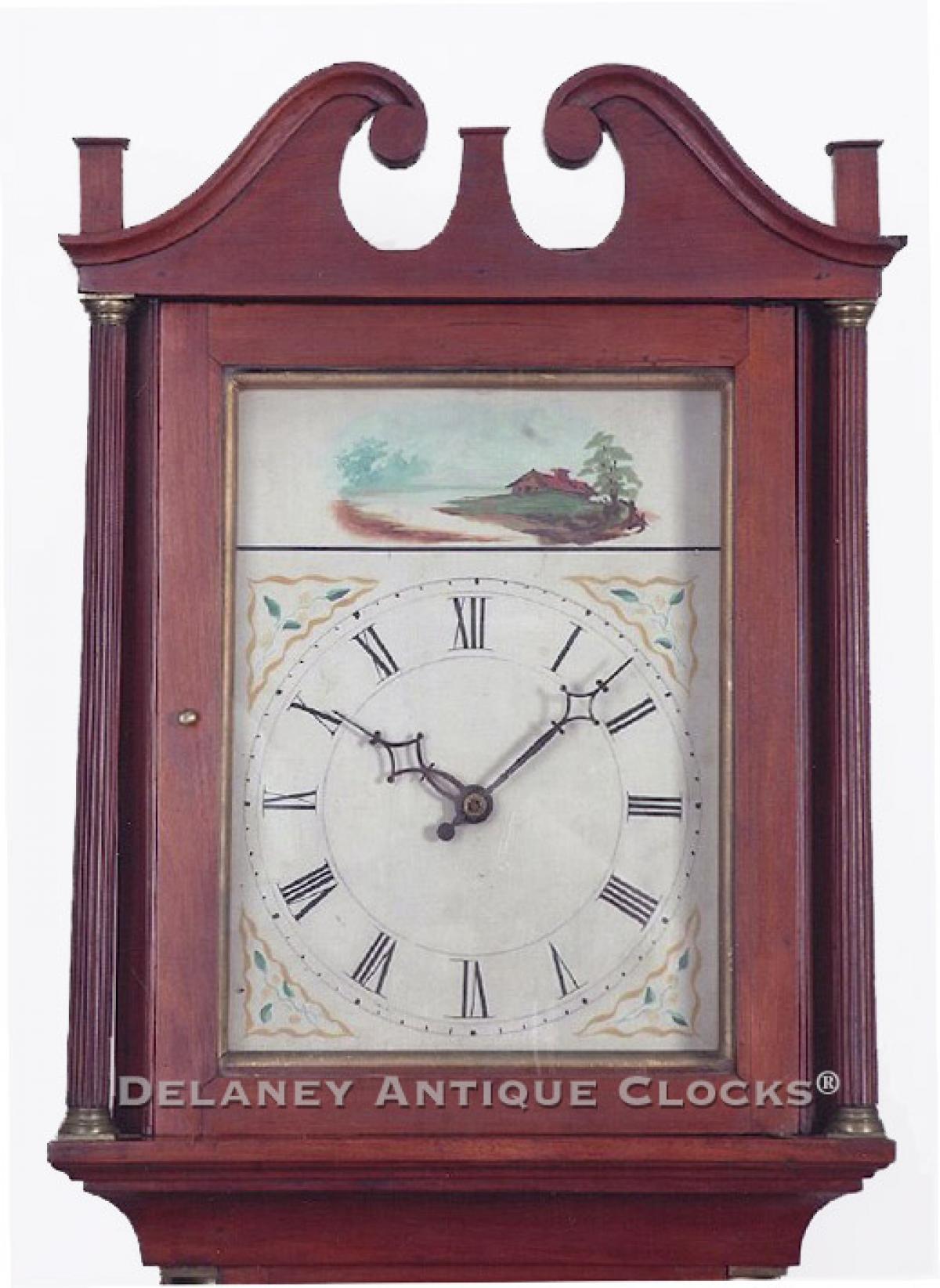

The rectangular-shaped wooden dial is framed by a simple molding that is decorated with gilt paint. The dial features a time ring that is formatted with Roman-style hour numerals. The four spandrel areas feature delicate floral designs. The upper section of this dial depicts a pastoral scene of a small home on the edge of a river.

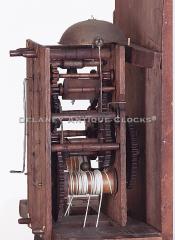

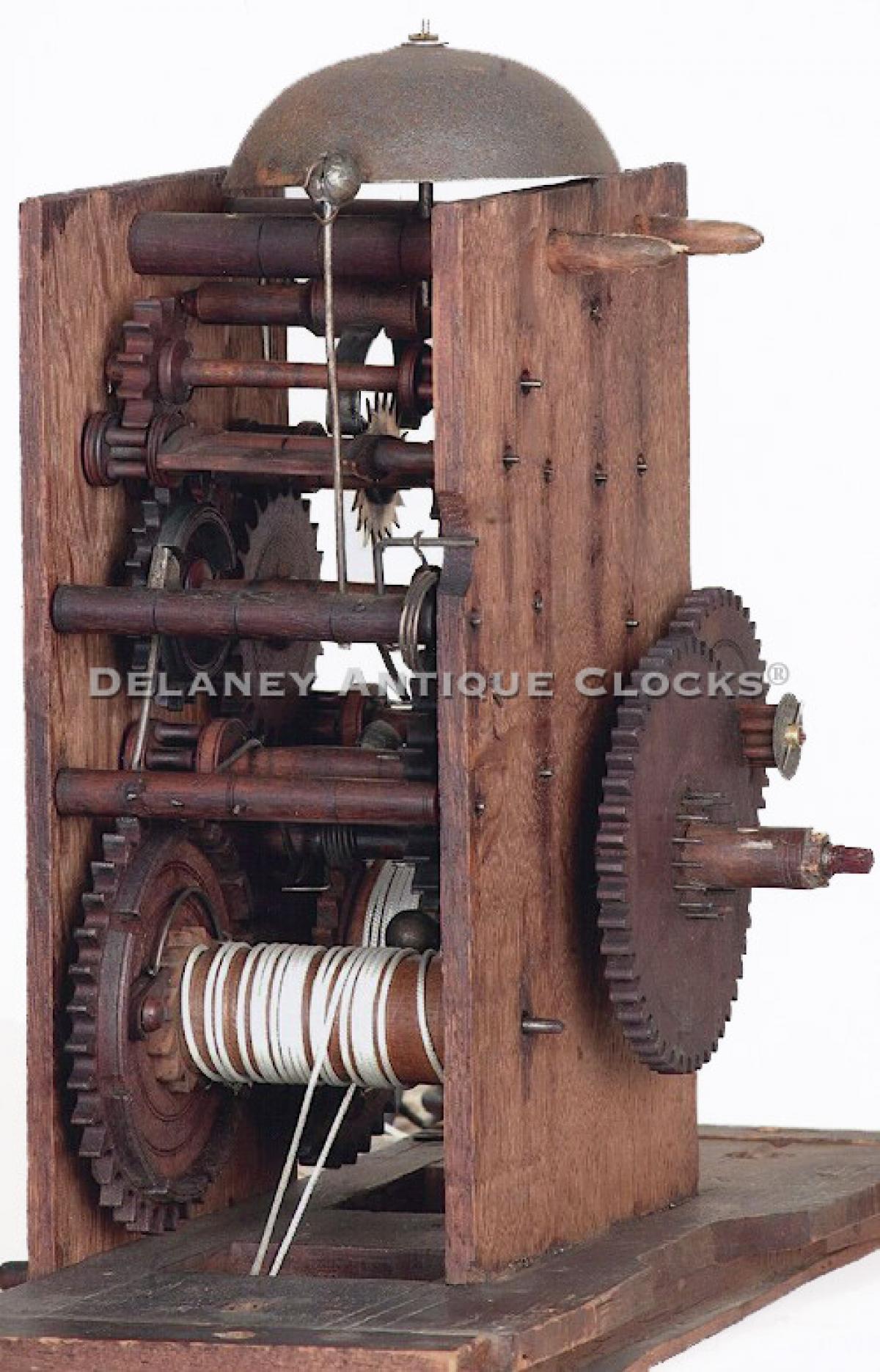

The movement is constructed in wood. Oak is used for the plates, cherry for the wheels, and mountain laurel is used to construct the roller pinions. The use of roller pinions was an Ives improvement in an attempt to reduce the amount of friction in the design of the movement. This clock is powered by weights and is designed to run for eight days on a full wind. The two drive weights are original to this example and are tin cans. These are filled with sand, rocks, and whatever else was handy. A pulley compounds the time train, so the barrel diameter on the train is larger to hold more cord. This movement is also designed to strike each hour on a bell.

This clock was made circa 1813 and stands approximately 7 feet 4 inches tall.

Joseph Ives sold his factory in the North Village of Bristol and moved to the South Village in 1818. There he joined Elias and Titus Merriman Roberts and established the Joseph Ives & Co. In this shop, he introduced his brass-wheeled roller pinion weight-driven movement, which, at his time, was considered remarkable. It was a clear departure from the standard wooden works movement production that was now standard for this region. Unfortunately, this venture went bankrupt on December 24, 1819. As a result, very few of these clocks were made, and a small number have survived in this wonderful condition. It is reported that this model originally sold for $33. This is twice as much as the $15 cost of a standard Terry wooden works clock.

Inventory number 23145.

Joseph Ives was born on September 21, 1782. He was one of six children born to Amasa Ives, who married into the Roberts family of Bristol, Connecticut. Gideon Roberts is recorded as the first clockmaker to have worked in Bristol, and it is now thought that he trained his five sons in clockmaking and possibly trained Joseph and his brothers in the trade as well. They all would have been trained before Gideon died of typhoid fever in 1813.

Joseph Ives began making wooden geared clocks about 1811 in East Bristol. Shortly after that, he moved to Bristol and continued in the trade. The type of clocks being manufactured was called “wag-on-the-wall” or hang-ups.” Peddlers who could carry a small number of them on horseback sold these across the countryside. A hang-up consisted of a movement, dial, hands, weights, and pendulum. They were generally sold without cases because of the added cost and the difficulty in transportation. As a result, most cases were made locally. Ives clocks are distinctive in that they typically feature rolling lantern pinions instead of leaf pinions in their movement design. This was an Ives improvement that was patented.

By 1820, Eli Terry was enjoying great success in selling the 30-hour wooden geared shelf clocks of his design. Terry’s clocks were powered by weights, and Ives began to experiment with a spring-powered version having roller pinions attached to a wooden movement. Due to financial difficulties, Joseph moved to Brooklyn, New York about 1825 and worked on Poplar Street. Here he begins the production of a movement constructed with rolled brass strips which are then riveted together to form the movement frame. Roller pinions and the leaf spring power are also used. The case of these clocks has a Ducan Phyfe furniture influence.

In 1830, Ives creditors caught up with him again, and he was on the verge of being sent to debtors prison. John Birge hears of this and travels from Bristol to Brooklyn to settle his debts and to persuade Ives to return to Connecticut to make clocks, first with C. & L.C. Ives, who were using his strap frame design and then with John Birge under Birge & Fuller name. This company used the leaf or wagon spring power in many clocks. This design of power was also patented by Ives.

Joseph Ives sold the rights to his patents and continued to work in the clock fields under various firms. He was never financially successful but is credited as one of the most ingenious Connecticut horologists. Joseph died in 1862.

For a more complete description of Joseph Ives and his working career, please read, The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810-1862, written by Kenneth Roberts.