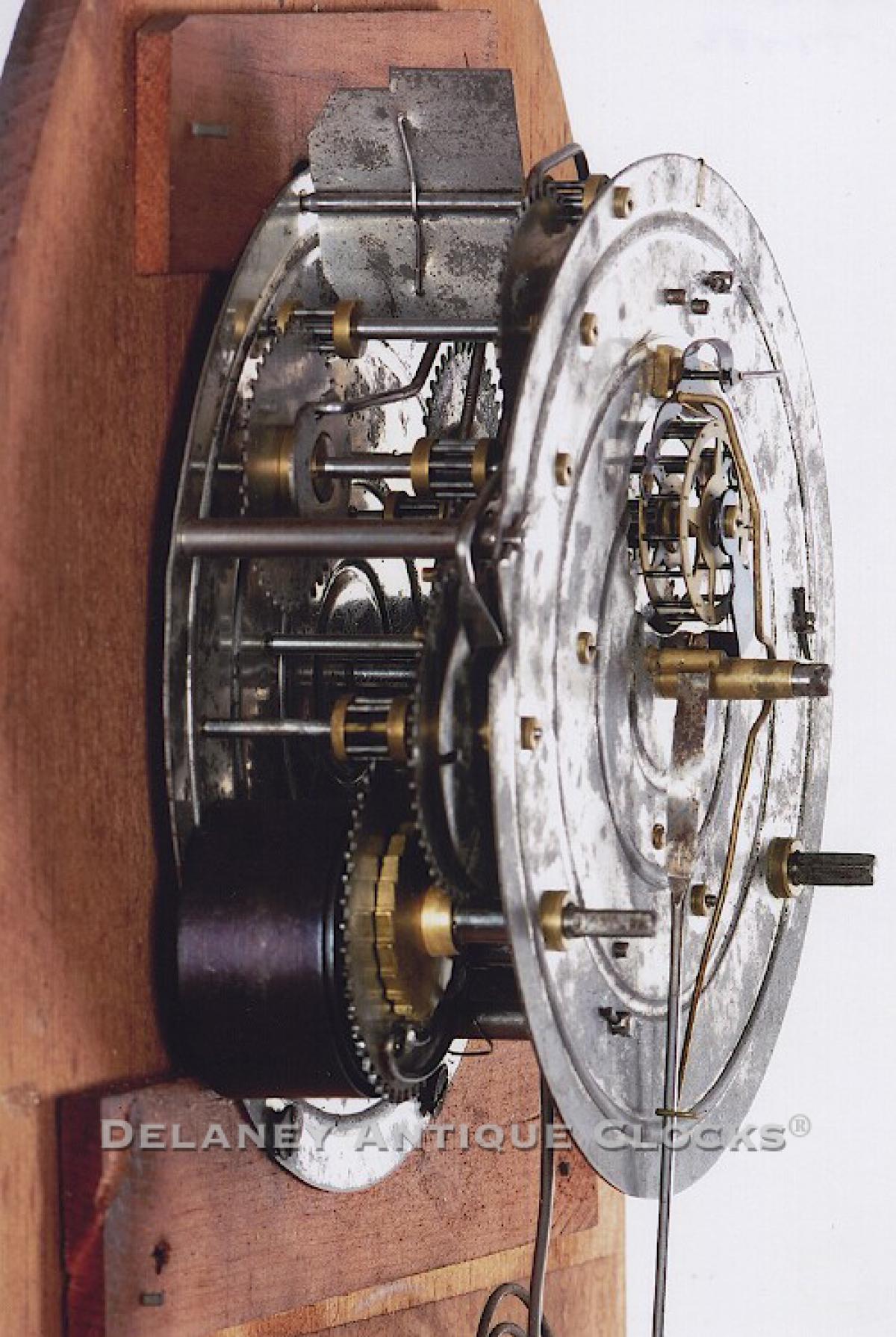

N. L. Brewster case with Joseph Ives Patent “Tin Plate” movement. TT-186.

Joseph Ives received a patent for this tin plate movement design on October 25, 1859. When he died in 1862, his estate inventory included 3,000 tin plate movements. To this day, not a single tinplate clock is known to exist with an Ives label. According to Kenneth Roberts' book, "The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810 - 1862," only two firms used this tin plate movement. They were N. L. Brewster and the E. Ingraham & Co., both companies, were located in Bristol, Connecticut. Interestingly, neither firm, in 1861, was manufacturing any of its own movements. They did manufacture cases, and it is from this case style that this clock is attributed to N. L. Brewster.

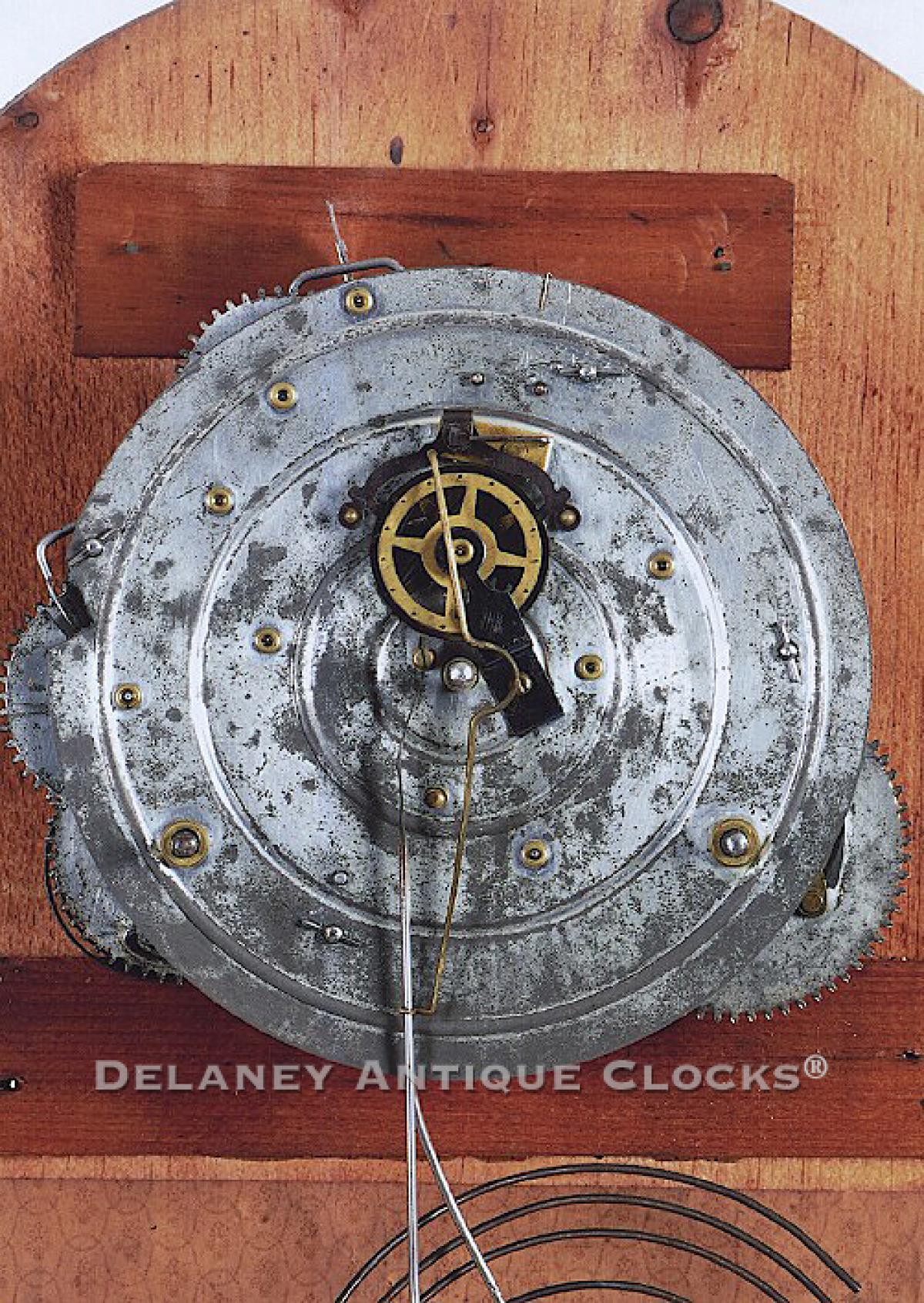

This rosewood veneered case stands 17.5 inches tall. It is 10.75 inches wide at the base and 4.5 inches deep. It retains what appears to be its original finish. Fully turned columns are applied to the sides and are joined at the top with a decorative pipe molding that conforms to the overall shape of the case. The front panel is fitted with a door. This door is divided into two sections. The lower panel is famed in wood and features a wonderfully paint-decorated tablet. Centered here is an American bald eagle depicted with outstretched wings, clutching four arrows in its left claw and a fruit tree branch in its right. A red banner is held in its powerful beak. The borders are done in gilt paint, highlighting the mustard yellow and the larger blue field. This tablet is original to this clock and has experienced some minor losses. Through this door, one can access the pendulum. You should also note the fine paper that covers the backboard. The upper section of this door is framed in brass and fitted with clear glass. Through this, one can view the painted dial that measures 6 inches in diameter. This dial is original to this clock and has had some restoration. The center of this dial is left open. Here one can see the movement for which Joseph Ives most likely made and is based on his last patent.

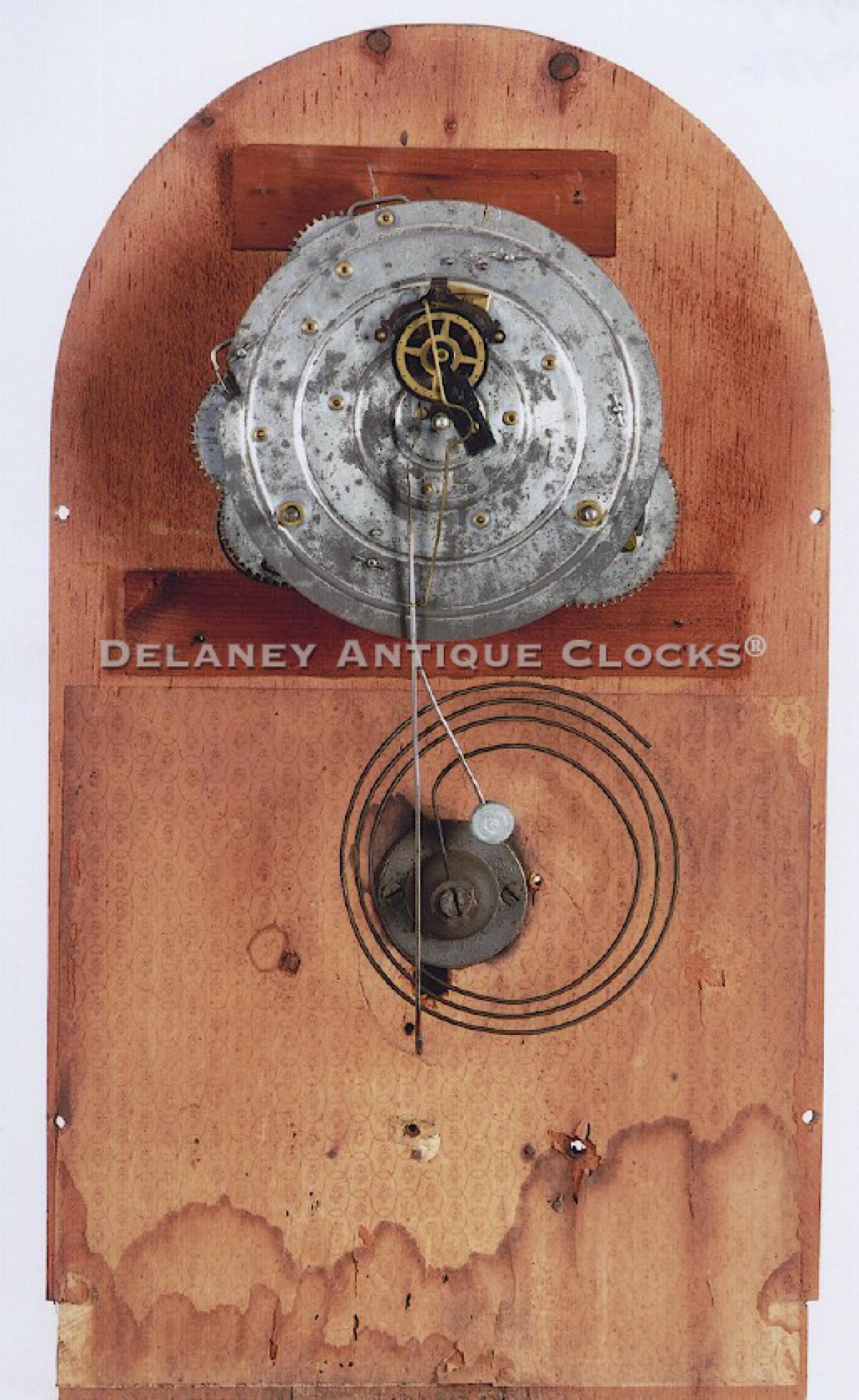

Ives was granted this Patent No. 25934 on October 25, 1859. One can see the "Squirrel cage" roller pinion crown wheel escapement and the front plate of the movement, which was tinned. This movement was originally advertised as never needing oil. It is powered by two coil springs that are designed to run for eight days fully wound. This clock also strikes each hour on a wire gong. N. L. Brewster incorporated this movement into his Venetian shelf clock circa 1860.

For a more in-depth discussion about this model, please read Kenneth L. Roberts' book, The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810 - 1862.

Inventory number TT-186.

Joseph Ives was born on September 21, 1782. He was one of six children born to Amasa Ives, who married into the Roberts family of Bristol, Connecticut. Gideon Roberts is recorded as the first clockmaker to have worked in Bristol, and it is now thought that he trained his five sons in clockmaking and possibly trained Joseph and his brothers in the trade as well. They all would have been trained before Gideon died of typhoid fever in 1813.

Joseph Ives began making wooden geared clocks about 1811 in East Bristol. Shortly after that, he moved to Bristol and continued in the trade. The type of clocks being manufactured was called “wag-on-the-wall” or hang-ups.” Peddlers who could carry a small number of them on horseback sold these across the countryside. A hang-up consisted of a movement, dial, hands, weights, and pendulum. They were generally sold without cases because of the added cost and the difficulty in transportation. As a result, most cases were made locally. Ives clocks are distinctive in that they typically feature rolling lantern pinions instead of leaf pinions in their movement design. This was an Ives improvement that was patented.

By 1820, Eli Terry was enjoying great success in selling the 30-hour wooden geared shelf clocks of his design. Terry’s clocks were powered by weights, and Ives began to experiment with a spring-powered version having roller pinions attached to a wooden movement. Due to financial difficulties, Joseph moved to Brooklyn, New York about 1825 and worked on Poplar Street. Here he begins the production of a movement constructed with rolled brass strips which are then riveted together to form the movement frame. Roller pinions and the leaf spring power are also used. The case of these clocks has a Ducan Phyfe furniture influence.

In 1830, Ives creditors caught up with him again, and he was on the verge of being sent to debtors prison. John Birge hears of this and travels from Bristol to Brooklyn to settle his debts and to persuade Ives to return to Connecticut to make clocks, first with C. & L.C. Ives, who were using his strap frame design and then with John Birge under Birge & Fuller name. This company used the leaf or wagon spring power in many clocks. This design of power was also patented by Ives.

Joseph Ives sold the rights to his patents and continued to work in the clock fields under various firms. He was never financially successful but is credited as one of the most ingenious Connecticut horologists. Joseph died in 1862.

For a more complete description of Joseph Ives and his working career, please read, The Contributions of Joseph Ives to Connecticut Clock Technology 1810-1862, written by Kenneth Roberts.