Oliver Wight of Sturbridge, Massachusetts. An important tall case clock. 212121.

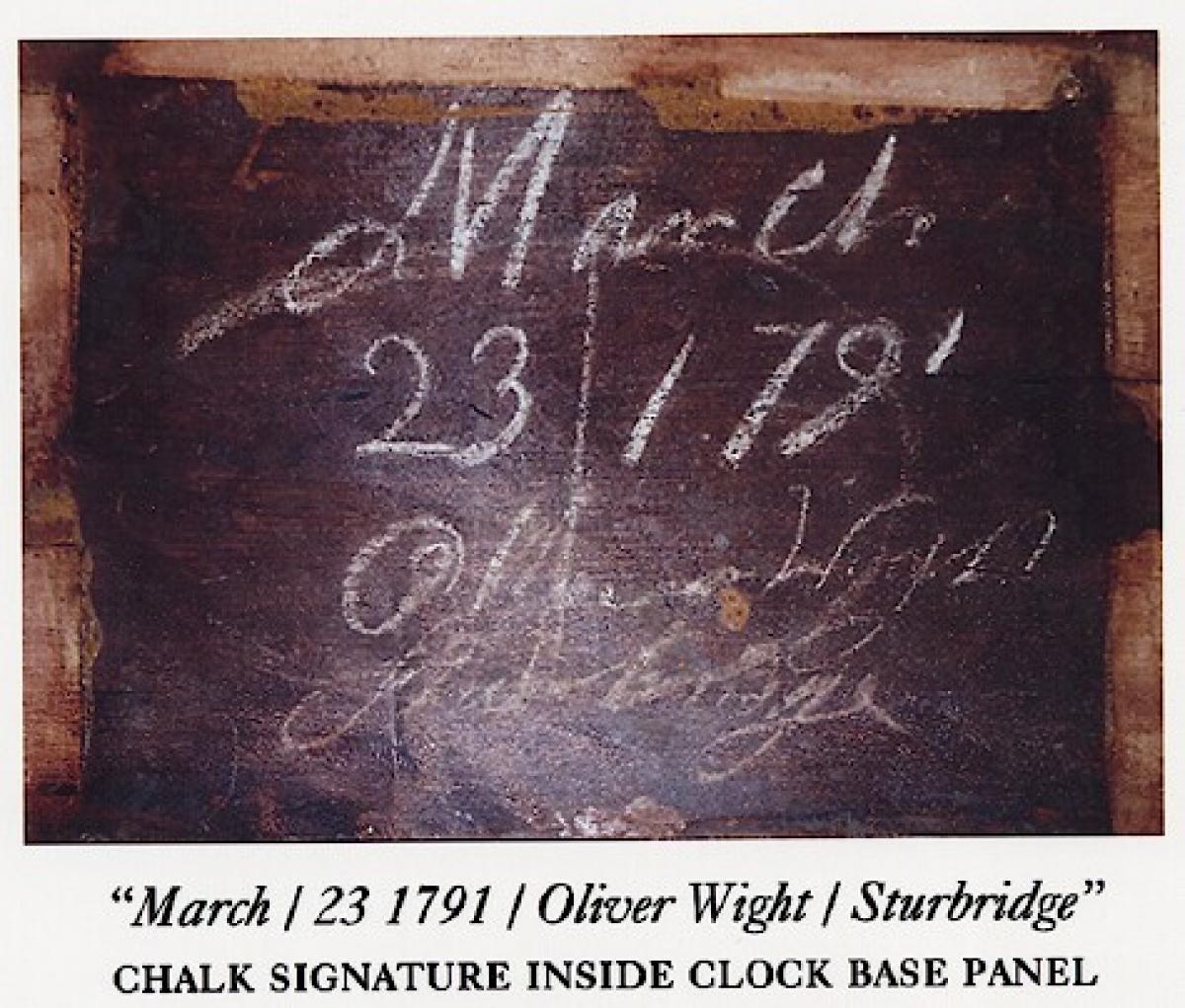

This important inlaid tall case clock was discovered by us and sold to Old Sturbridge Village in 2012. We realized the importance of this example to this fine living museum and encouraged them to purchase it. At the time, it was the only signed piece of furniture by this Sturbridge, Massachusetts, cabinetmaker. This example is signed inside the base panel in chalk by the cabinetmaker. It reads, “March 23, 1791 / Oliver Wight / Sturbridge.” This is a remarkable find. Very few clock cases are signed by their case maker. Even fewer are signed by historically important individuals. The discovery of this signature helps tie Oliver to what would become the Sutton, Massachusetts, school of cabinetmakers that includes Nathan Lombard.

This example exhibits the best country form with excellent proportions and eye-catching inlays. This tall clock case is constructed in cherry, and New England white pine is used as a secondary wood. The inlays are comprised of mahogany and maple selections. The case features an appropriate orange shellac finish that promotes the texture, contrast in color, and grain exhibited in the selected wood. This case stands on boldly formed ogee bracket feet. The profile of the knees and returns are nicely exaggerated. These are applied to a molding that is secured to the base. The base panel is framed with a narrow cross-banded mahogany border and a lighter maple banding. Each of the four corners of this panel are fitted with quarter fan inlays. These fans are constructed with eight individual petals of alternating wood comprised of darker mahogany and lighter-colored maple. The top portion of an eight-pointed star is formatted similarly and can be found featured in the center of the base panel. The design of this star and the choice of woods provides a visual illusion of being three-dimensional. The waist section is long and is fitted with a tombstone-shaped waist door. This door features the same banded border featured on the base panel. This pattern is also used on the bonnet or hood door. The center of the waist door is inlaid with a fan that is constructed with twenty individual petals. Because the cabinetmaker used an even number of petals, the design starts in a light color maple wood on the left and fans to a dark shade of mahogany on the right. It appears to be out of balance. This is because the mahogany coloring competes with the cherry color of the door and gives one the illusion that the fan is missing a petal on the right and is therefore tilted. This is not the case. When one approaches the cabinet, the delineation of the two kinds of wood becomes more visible, and the fan shifts visually to an upright position. One can access the original tin can weights and brass-faced pendulum bob through this door. The front corners of the waist are fitted with fluted quarter columns. These terminate in turned wooden quarter capitals. The bonnet or hood is equipped with a traditional New England-style pierced fret. This somewhat unusual pattern has design elements that are seen in other Central Massachusetts examples. Three fluted chimneys or final plinths support this fretwork. Each of the plinths is capped and supports a brass finial. Fully turned and fluted bonnet columns visually support the upper bonnet moldings. These are mounted in brass capitals and are free-standing. The bonnet moldings are complex. The addition of an architectural detail referred to as Greek key molding is incorporated into this molding. This decorative detail is rarely found in American tall-case clocks design. The sides of the hood feature tombstone-shaped side windows. The arched bonnet door is also lined inlaid. It is fitted with glass and opens to access the painted iron dial.

The imported English dial has a Wilson false plate. It features a moon phase or lunar calendar mechanism in the arch. The time track is formatted with Roman-style hour numerals separated from the Arabic five-minute markers by a dotted minute track. A subsidiary seconds dial and month calendar are inside the time ring. The four spandrel areas are colorfully paint-decorated with fruits, florals, and berries.

This fine movement is constructed in brass and is of good quality. Four-turned pillars support the two brass plates. These pillars are unusual in that they incorporate a cone design in their structure. This may be a clue as to the origin of the movement. Hardened steel shafts support the polished steel pinions and brass gearing. The winding drums are grooved. The escapement is designed as a recoil format. The movement is weight driven and designed to run for eight days. It is a two-train or a time-and-strike design having a rack and snail striking system. As a result, it will strike each hour on the hour on a cast iron bell mounted above the movement.

This tall clock was made in March of 1791. It stands approximately 92.5 inches or 7 feet 8.5 inches tall to the top of the center finial. This case is 21 inches wide and 11.25 inches deep at the upper bonnet molding.

Inventory number 212121.

Oliver Wight was born in Medway, Massachusetts, on September 27, 1765, and died in Sturbridge on October 22, 1837. His parents, David Wight, born August 16, 1733, and Catherine Morse, born March 5, 1737, were both originally from Medfield, Massachusetts, and married on June 19, 1760. They settled just west in Medway immediately after their marriage. Six years later, they erected a house on the great road in that town and opened it for public entertainment. Here they remained until they sold this property in 1773. In that year, they purchased 1000 acres of land in Sturbridge. Approximately 40 miles west, Sturbridge was at that time considered wild wilderness. By 1775, Mr. Wight and his three boys, David Wight 2nd, Oliver, and Alpheus, had cleared enough land to grow grains and grass, and with this move, they became one of the first settlers of this town.

At the age of 21, Oliver married Harmony Child in Sturbridge on July 5, 1786. They had eleven children and enjoyed a brief period of prosperity.

Like his brothers David and Alpheus, Oliver acquired property from their father, who held expansive property holdings. In 1789, Oliver and Harmony were thought to have had the housewright Samuel Stetson build their Georgian-style dwelling. This clap-boarded homestead featured a hipped-gable roof, two interior chimneys, and a ballroom on the second story that spans the front of the building. This impressive building is now part of the Old Sturbridge Village (OSV) complex. It is one of only two buildings on the OSV property that stands on its original site and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. Here, Oliver also constructed a sizable shop. Oliver was an ambitious cabinetmaker. He is said to have built chairs, tables, chests, bedsteads, and other household furniture. He is recorded as advertising his wares in the Massachusetts Spy, a newspaper published in Worcester, MA. An advertisement placed on June 13, 1793, “Respectfully informs the Publick, THAT he carries on the CABINET and CHAIRMAKING BUSINESS in its various branches...” Another sign of their prosperity is the couple’s portraits which are currently located in the collections of The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum at Colonial Williamsburg. These portraits are thought to have been painted by Beardsley Limner. Financial troubles soon followed the Wight family sometime around 1793. Deputy Sheriff James Upham took out an advertisement placed on September 5, 1793, in the Massachusetts Spy. This notice claims that Oliver had absconded and that on the 23rd of that month, He was going to sell “A PRETTY affortment (assortment) of Cabinet Work, Houfehold Furniture, Hard Ware, and many other Articles, too numerous to Mention...” in order to eliminate three hundred and fifty (British) pounds of debt. In 1795, the family was forced to sell the house. Oliver relocated to Providence, Rhode Island, and in April of 1802, the Massachusetts Spy reported that Oliver was to face the court and was bankrupt.