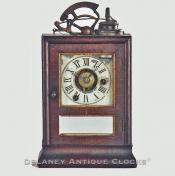

Seth Thomas. An Illuminating Alarm Clock. PROCTOR’S PATENT. BURGLAR AND FIRE-DETECTIVE CLOCK. PATENTED AUGUST 7, 1860. SS-10.

This clock answers the triple purpose of a Time-piece, a Burglar, and a Fire Alarm and lights a lamp at the moment the Alarm Strikes.

This is not your usual Seth Thomas-made 9-inch cottage clock having a flat top and an OG base model. This basic form was put into production as early as 1852. It was made in significant numbers, suggesting it was successfully sold. The model discussed here is a notable example in that it has been fitted with Proctor’s Patent Mechanism. Proctor’s patent was a device designed to be used as a burglar or fire alarm. Proctor was granted his patent on August 7, 1860.

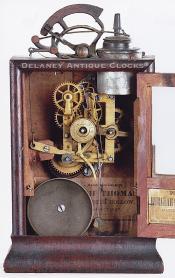

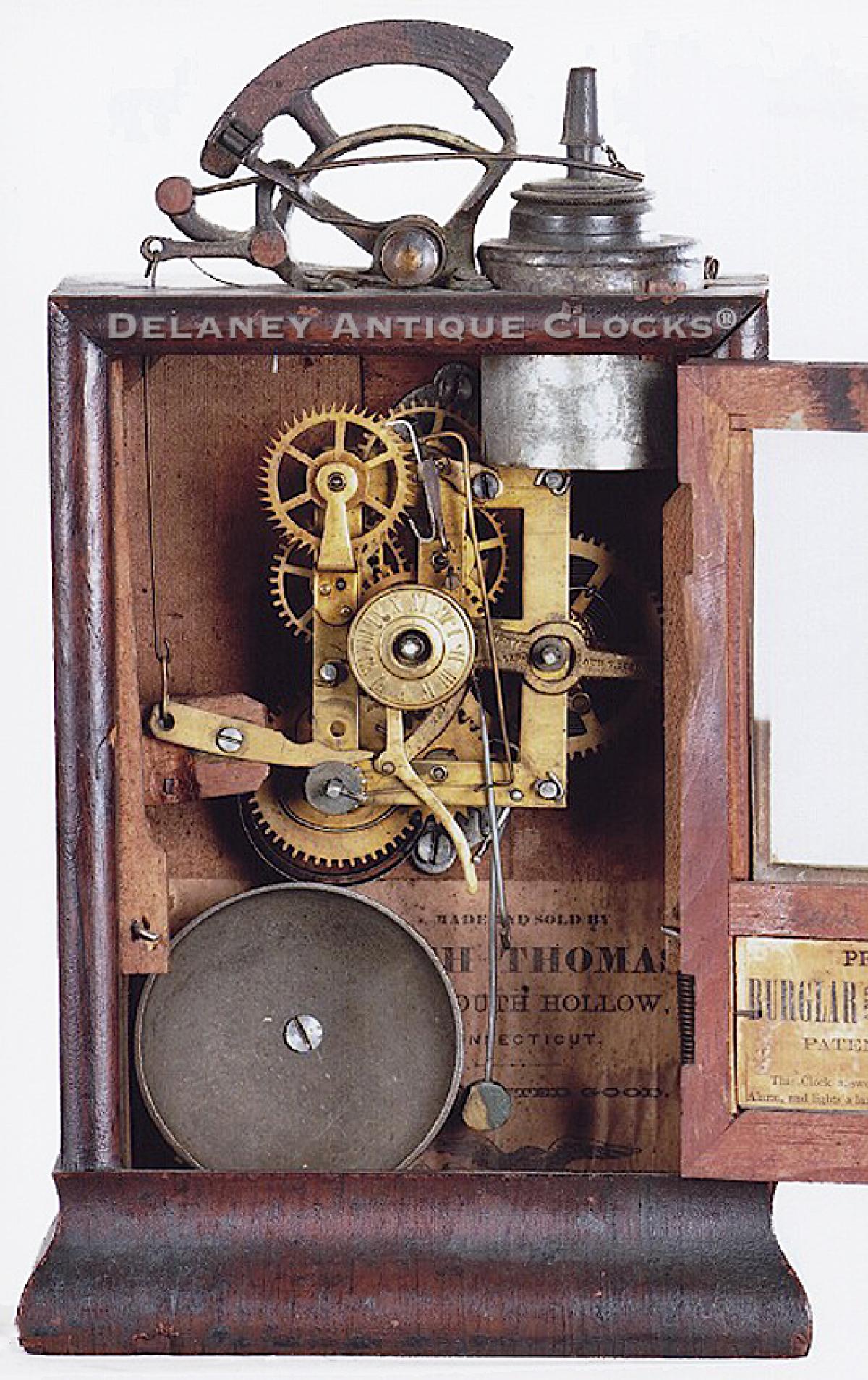

The case is a standard Seth Thomas 9-inch Cottage clock case. It is veneered in rosewood and retains an original finish that has darkened considerably with age. The movement is also Seth Thomas made. It is spring-powered and designed to run for 30 hours when fully wound. It also features an alarm. The alarm uses a hammer that hits a cast iron bell. This bell is mounted inside the movement to the backboard with a single screw. This is a standard setup. The Maker’s label is pasted onto the backboard inside the case. This is the 1854 label. Owen Burt categorizes this as a “rare” label in his book entitled, “SETH THOMAS 9” COTTAGE CLOCKS 1852-1898.” Proctor’s edition includes the strike plate in the form of an arch fitted to the top of the case, the actuating arms that connect it to the movement, and the oil lamp.

How does it work? The spring-tensioned arm is loaded and locked into place. A match is inserted into the end. The firing tip of the match is positioned against the strike plate so that when the arm is released, the match head rubs against the strike plate and lights or fires. The arm then positions the match head over the oil lamp, lighting the burner.

To use the burglar alarm. Behind the lamp protruding through the top of the case is a small wire with a loop at the top. Its’ purpose is to have a string attached to it. This end of the wire is connected to the movement as a release. The other end of the wire is tied to or connected to the door or window you wish to protect. The string transfers the movement of the door or window via the wire. The tension in the wire triggers the mechanism, causing the match to rub against the strike plate, lighting the lamp. This is the signal that someone has moved the door or window. The lamp will illuminate the room.

To use the fire alarm. The fire alarm uses the same principle of tying a wire loop at the top of the clock to a fixed object. The difference is that the area protected is under the line. (This is great.) So, the idea is that if there is a fire under the string, the string will burn, releasing the mechanism in the clock. This action activates the mechanism and lights the oil lamp.

We have seen several variations of this design on numerous clock forms, including a steeple clock and several other versions of cottage cases. Various Makers made these examples. I have to believe that many of these novelty clocks have burned up over the years. It is easy to imagine that the match could be easily thrown across the room because it wasn’t secured adequately. Or that the clock may vibrate off the table, chest, etc., while broadcasting the alarm. The result would be a split oil lamp on the floor.

Inventory number SS-10.

Seth Thomas was born in Wolcott, Connecticut, in 1785. He was apprenticed as a carpenter and joiner and worked building houses and barns. He started in the clock business in 1807, working for clockmaker Eli Terry. Thomas formed a clock-making partnership in Plymouth, Connecticut, with Eli Terry and Silas Hoadley as Terry, Thomas & Hoadley. In 1810, he bought Terry’s clock business, making tall clocks with wooden movements. He chose to sell his partnership in 1812, moving in 1813 to Plymouth Hollow, Connecticut, where he set up a factory to make metal-movement clocks. In 1817, he added shelf and mantel clocks. By the mid-1840s, He successfully transitioned to brass movements and expanded his operations by building a brass rolling mill and a cotton factory. His clock business expanded until it became one of the “BIG Seven” in Connecticut and competed at every price point, from kitchen clocks to precision regulators. He made the clock that is used in Fireman’s Hall. He died in 1859, at which point the company was taken over by his son, Aaron, who added many styles and improvements after his father’s death. The company went out of business in the 1980s.